You are responsible for the consequences of your speech (Yes, really).

I have a spicy take for you today, bunnies, but a version of it was actually published with proper peer-reviews and all, so fight me about it.

You communicate the predictable interpretations of your speech.

“Wait what Llwyn? If I say something and someone interprets it in a way that causes them offense, I actually communicated an offense? Even if I didn’t mean to offend them? What the hell is wrong with you Llwyn?”

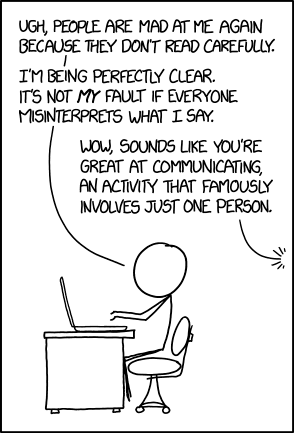

xkcd strip 1984: Misinterpretation

Keep calm, take a deep breath, let me explain. But also, yes.

Speech and intention recognition

We touched on the complex issue of intention recognition and intention attribution when we did a quick dip in the wonderful world of implicatures. It has been a while though, so let’s recap the problem.

Humans, it seems, are not telepaths. It’s kind of the whole reason why we use language to communicate reasonings, intentions, emotions, requests, etc. Language is a great way to coordinate with other people!1 And it also enables us to recognize that other people have emotions, intentions, reasonings, needs, that may differ from our own. Wonderful thing, language. But I am obviously biased.

Crucially, we have very little insight other than language in other people’s internal lives. We have to take what they say, and assume that it’s somehow connected to what they think and feel. The Gricean Maxims of Conversation come in play once again: in a conversation, we commit to behaving as if the others are being sincere, relevant, and making good use of their speech. That’s how we assume, or infer intentions from others’ speech in general. I have no way of knowing what beliefs you hold, what intentions you have. But for communication to even be possible, I have to assume that, when you say “Close the window!”, you intend for me to get up and close the window.

Now, intention recognition can lead to misunderstandings. Maybe you didn’t actually wish for me to get up and close the window right away, and you actually meant “Remember to close the window when you leave”. There we are: are you responsible for an interpretation I made, when it was not the interpretation you intended for me to make?

Oh boy, we’re in it for a ride.

Speech Acts

The first thing to clarify is that discourse contains actions, for which a speaker may be responsible.

Most of y’all are familiar with the concept of responsibility for one’s actions. It ties in with accountability. If you accomplished an action, you may have to explain it, justify it, and at the bare minimum assume the role of person who accomplished the action.

Somehow, lots of people don’t include speech in their actions that they are responsible for. To me (and a whole cohort of linguists), this is bonkers. Why? Well, because we have this little field of study called Pragmatics. The idea behind pragmatics is that speech affects the world around us, and can be analyzed in terms of speech acts: actions that are conducted with speech.

The foundational work on Speech Acts is Austin’s 1955 William James Lectures, edited and compiled in How to do things with words. I generally refer to the 2d edition, Urmson and Sbisà did a wonderful job correcting and annotating the text from Austin’s notes. Another big contender is Searle’s 1975 Speech Acts book. I don’t agree with some of Searle’s discussion of language rules, but it’s a milestone. Or, if you’re looking for the novelized version, Laurent Binet’s The Seventh Function of Language is an entertaining thriller about the power of language in 1980s French theory. With spies and murder.

What’s the big deal, then? The main thesis of Austin’s work is that, when people speak, they are performing actions. Describing the world around you is an action. Convincing someone is an action. Giving an order is an action. Asking a question is an action. These actions affect the world around speakers. They change it.

Austin has two lovely examples to highlight how speech modifies the world around a speaker (paraphrased here).

At the wedding, the officiant proclaims: “You are now married”.

The officiant has changed the world, according to a procedure they have the authority to conduct, and modified it so the spouses’ marriage is now a fact of the world.2

Before the first travel of the new ship, the government official breaks a bottle on the ship’s stem, and states the ship’s name.

The government official has made it so that the ship is now named.

These are two examples of what we call the performative aspect of speech: the aspect by which speech modifies the world around it, and changes reality. Explicitly performative speech acts generally require a procedure to be followed, and that the speaker has the authority to conduct the procedure.

However, garden variety speech is also rife with performatives (generally more implicit).

Avi: “I gift you this sweater”

Bell: “I promise to take good care of it”

Here, the two participants have performed speech acts by which they (respectively) change the owner of the sweater and undertake an obligation to appropriately care for the sweater. These acts have changed the structure of ownership of the sweater (resp. obligations towards the sweater) by introducing new commitments. Avi commits to now treating the sweater as belonging to Bell, Bell commits to now caring for the sweater appropriately.

“Okay, Llwyn, I follow you. But you also mentioned that a descriptive speech contains an action, and I don’t really see how, if I say it is raining, I am changing the world around me?” Man, you’re really smart! Have a cookie.

Austin’s definition of speech acts focuses on performative speech acts, speech acts that, in virtue of being performed have an effect during their performance. That is: the officiant’s words are the procedure by which the spouses are wed. But, generally, all speech can be analyzed as constituting of two, or three actions:

- a locutionary act, which is roughly equivalent to the action of uttering a sentence that has a certain meaning.

- an illocutionary act, which is equivalent to the action that we conduct by uttering a sentence: we inform, we ask, we order, we warn.

- (optionally) a perlocutionary act, which is what we bring about by uttering a sentence: convincing, persuading, deterring, obtaining an answer, etc.

Now, even if you didn’t succeed to persuade your audience to bring an umbrella by saying it is raining, you have still done two actions: said that it was raining, and informed your audience that it was raining. By doing so, you have modified the world around you: you have (1) issued sound waves that express a meaning to the effect of describing a raining state of the world, (2) changed your audience’s beliefs to introduce the belief that it’s raining, (3) undertaken a responsibility towards your audience, that they can refer their belief that it is raining to your statement. In other words, you have conveyed to your audience that they can use trust your statement as a basis to believe it is raining. That’s pretty fucking powerful, if you’ll ask me!

Speech Acts and Commitments

So, how is a speaker responsible for their speech acts? Well, pretty much the same as for normal acts. A speaker authors speech acts, and in this sense they incur various obligations under the assumption that they are a cooperative speaker.3 Brandom wonderfully analyzes speakers’ responsibilities in terms of commitments:4 by describing the world with the sentence It is raining, a speaker commits to be liable for their statement. They may have to provide justification when they are asked about it. They also commit to behaving in a manner consistent with what they said – a speaker saying It is raining and following up with Let’s go enjoy the sun would raise a few eyebrows.

Brandom is an expressivist, a current in philosophy of language that starts around Blackburn.5

Blackburn coins expressivism in the field of meta-ethics, by holding that statements like This is good cannot be analyzed

as describing the world according to the speaker. Rather, they should be analyzed as expressing an attitude of approval from the speaker.

Brandom generalizes the take, in that he says that all statements, including informative ones, express attitudes of the speaker.

In the case of it is raining, a willingness to commit to the justification of this statement, and act accordingly.6

This commitment to one’s speech is part of the illocutionary act that one conducts when they assert a sentence. In addition to informing someone, they undertake the commitment to justifying their speech if so pressed, and to introducing their utterance in their reasoning. These commitments come with responsibilities, in that speakers’ can be asked to justify what they asserted, and sometimes to answer for the consequences of their assertion. Or, in plain terms: ordering coffee involves a commitment to pay for it, and an understanding that it will be prepared for you. Asserting that it is raining involves that you are responsible to explain why you said so if your audience finds clear skies when exiting the building.

Note, here, that asserting something carries more responsibility than merely communicating it. Content is asserted when it is presented as communicating a representation of the world or the speaker’s knowledge. When I say It is raining, I make this statement with an illocutionary force that represents the state of affairs as being a raining state of affairs. Contrast this with If it is raining, I shall bring an umbrella, which does not communicate that it is, in fact, raining.

On the other hand, some contents can be merely communicated. Presuppositions, or implicatures, are not asserted, but merely communicated by speech. In My damn bike has a flat, I am not asserting that I dislike my bike, but I am sure communicating it.

Asserting something involves being recognized as the person who made the assertion, having to answer for it, being able to retract it, and allowing others to take you as an authority to ground their reasonings on this assertion, or repeat it. On the other hand, merely communicating a content involves being recognised as the agent that made this communication, and that has authority to modify it, clarify it. However, you do not undertake as much justificatory responsibility.7 Note that neither responsibility involve moral blameworthiness. Rather, they cover “what can reasonably be asked of the agent that carried a communication, and what intention can be imputed to this agent”.

Why am I responsible for the way others interpret my speech?

“Fine, Llwyn, when I speak I am committing to my speech and thus undertaking some obligations and gaining some rights as the author of an utterance. But, if someone interprets what I said, did I actually communicate what they interpret? Am I also responsible for their interpretation of my speech, even if I didn’t intend it? That sounds like a lot!”

Yes, bunny, it does sound like a lot. Let me explain. You’re right to notice that intent ties into communication, as to say that someone communicated something generally requires ascribing them an intention to perform a communicative act by their speech. A toddler stringing together syllables for their acoustic enjoyment, if they produce by accident a coherent English language sentence, is not taken to have communicated the content of their accidental sentence. On the other hand, most members of a linguistic community (competent speakers) are subject to a communicative presumption:

The communicative presumption is the mutual belief prevailing in a linguistic community to the effect that whenever someone says something to somebody, he intends to be performing some identifiable illocutionary act. (Bach and Harnish, 1979, p. 12)8

But, see the introduction, and the fact that humans are not telepaths: intentions are not transparent. We have to reconstruct, and recognize, a speaker’s intentions from their speech.

How do we do that? I ask, once again, Grice for help on the matter:

Explicitly formulated linguistic (or quasi-linguistic) intentions are no doubt comparatively rare. In their absence we would seem to rely on very much the same kinds of criteria as we do in the case of nonlinguistic intentions where there is a general usage. An utterer is held to intend to convey what is normally conveyed (or normally intended to be conveyed), and we require a good reason for accepting that a particular use diverges from the general usage (e.g. he never knew or had forgotten the general usage). Similarly in nonlinguistic cases: we are presumed to intend the normal consequences of our actions. (1957, p387)

There is a lot, here, but the gist is that we rely on generally established (conventional) use of speech to determine a speaker’s intent in producing a speech.

In other words: if you let go of a glass, and I know you are aware of how gravity works, I will assume that you intended for the glass to make a short trip towards the ground, and crash. If you tell me “Close the window”, and I know that you are a competent English speaker aware of how imperatives work, I will assume that you intended to order me to close the window. Or, to tie it with our discussion of speech acts: if you utter a sentence that is normally used to perform a certain speech act, I will assume that you intend to perform that speech act. This is what actually allows us to communicate anything:

- Say I mean to communicate content p.

- For this to work, the audience has to ascribe me the intention to communicate content p on the basis of my speech.

- As a competent speaker, I can make this happen, by using lexical items that are generally (in the community), used to communicate p.

For example: Beware, there are bees! is generally used to communicate to an audience that there are bees, and they should be careful in the area.

- When I use these lexical items, the audience reconstructs my communicative intention on the basis of what the lexical items are generally used to communicate.

For example, the audience interprets that I use Beware to communicate a warning, as it is generally used to warn others from a danger.

But maybe I actually meant to warn my audience to look out for the pretty bees? Crucially, the last point only matters if I have made it known that I use Beware as a general attention grabbing item, instead of a warning.

This is where a different responsibility than assertive responsibility comes into play. When a lexical item is generally taken to communicate a certain intention, it is my job, as a competent speaker, to be aware of the general use of an item, and be aware that I will be ascribed intentions on the basis of my use of a lexical item. Or, I didn’t mean it that way does not mean that I didn’t communicate it, and it does not mean that my audience is unreasonable in ascribing me the intentions that what I said is generally used to convey.

Let’s see if I have a decent example somewhere.

I want to meet with Patricia for drinks. I call her: ‘Let’s meet at the Descartes bar and go for drinks!’.

The reason why I suggest the Descartes is that, albeit closed, it is ideally situated for a meeting point – close to the metro, good parking spots, etc. Other nice bars are in the same street.

I make this proposition under the assumption that Patricia knows that the Descartes is closed. This is where I am wrong: she is not from the same neighbourhood, and doesn’t know the Descartes is closed.

My intention to communicate a meeting point is recognized: Patricia correctly judged that I suggested the Descartes as a meeting point. However, she also ascribed me the intention to communicate that we would have drinks at the Descartes specifically. It was a perfectly reasonable intention to ascribe me given her knowledge state. Thus, I can be said to have, albeit unknowingly, communicated to Patricia that we would drink at the Descartes.

Not all interpretation is up for grabs. There is no conventional meaning by which Patricia may reasonably ascribe me the intention to go canoeing, for example, unless previously agreed upon by both of us. But considering that, in context, the utterance: ‘Let’s meet at the Descartes and go for drinks!’ is generally used to communicate that one wishes to have drinks at the Descartes specifically, Patricia’s assumption that I intended her to understand that we would drink at the Descartes is fair game. And thus, I can be said to have communicated it, and be required to amend it.

What about misinterpretations?

Yeah, they happen. The fun part is: they happen all the time, we’re just really good at repairing them. When a speaker makes utterances, we interpret them on the basis of what we believe is a shared context. Sometimes, the context is not as shared as we thought. In which case, speakers may be asked to clarify what they actually intended to communicate, or even retract things they did communicate, but did not mean. And audiences may have to update their understanding of the way the speaker uses conventional meanings: a botany professor will not use berry in the commonly accepted way, instead reaching for the botanical definition of them – strawberries are not berries, but bananas are.

Non-conventional uses of words happen all the time, but they involve a responsibility for speaker and audience to agree on a conventions to properly resolve intention ascription.

On the other hand, speakers who consistently use lexical items that communicate something they do not mean may have to brush up on what the words they use mean, and improve their linguistic competence.

tl;dr

If you use speech that is generally understood to be offensive, people will think you meant to offend them. And they are reasonable in doing so. Don’t act all shocked pikachu face about it, and apologise already.

-

That includes sign languages, written and spoken languages, formal languages, artificial languages. Hell, even programming languages have a coordinating purpose and can express intentions and requests. ↩︎

-

Very sweetly, there were two occurrences in which an officiant changed my identity by their speech, and then claimed the honor to be the first to address me under this new identity. “I confer upon you a Doctorate. Allow me the honor to be the first person to address you with your new title of Doctor” and “I declare you married, allow me the honor to be the first to address you as spouses”. ↩︎

-

Remember what we said about cooperation: conversations are not all cooperative. Speakers are not all cooperative. But the cooperation assumption governs our expectations, and the way we interpret others’ speech. The person who said It is raining may be lying – but they can only lie under an expectation of sincerity. That’s the paradox of non-cooperative conversations, which I’d love to get into soon, that they exist because there is a backdrop assumption of cooperativeness. ↩︎

-

For Robert Brandom, I refer to ‘Asserting’ (1983), Noûs 17:4 and Making it explicit (1994). ↩︎

-

Spreading the Word (1984). ↩︎

-

I do realize I will probably have to do a deeper dive into expressivism eventually, because moving away from a truth grounded take on language to an attitude grounded take raises questions, and there is a lot of debates and cool research on it. ↩︎

-

My rule of thumb to determine conversational responsibility is “Can I retract it?”. As such, I carry responsibility for my speech and its reasonable interpretation by others. I do not carry responsibility for willful misinterpretation and the consequences thereof – more on that in the next section. ↩︎

-

Linguistic communication and speech acts ↩︎